Blocking issues aren’t the only challenges that may add extra time to rehearsals. Here are some other things to consider:

One or two roles that carry the lion’s share of the play. This includes two-handers, star vehicles, and wordy plays. Some plays just seem to have a lot more words in them than others, and even if there isn’t one character with more than anyone else, there may be several who have more than the lead in an average play. Plays like these typically require an extra week, just for memorization purposes.

Complex characters. Plays with one or two roles that are particularly complicated and challenging characters probably take a little extra time to allow for the actors to do them justice. Conversely, a well-balanced play with straightforward characters and actors who seem to be typecast in their roles may require a little less time to rehearse.

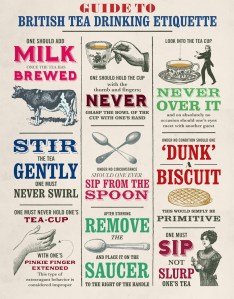

Military, period pieces. Some plays require body movement that is different from what we ordinarily use in real life. Plays like A Few Good Men, where the majority of the characters are in the military, means that the actors need to learn military bearing in how they stand, walk, etc., and to maintain that consistently throughout the play. Similarly, the manners at the Elizabethan court in Mary Stuart as well as the difference in attire will affect how actors need to move.

Military, period pieces. Some plays require body movement that is different from what we ordinarily use in real life. Plays like A Few Good Men, where the majority of the characters are in the military, means that the actors need to learn military bearing in how they stand, walk, etc., and to maintain that consistently throughout the play. Similarly, the manners at the Elizabethan court in Mary Stuart as well as the difference in attire will affect how actors need to move.

Physical ailments. An actor who needs to limp, pretend to be paralyzed, use a wheelchair, or make any other notable physical movement changes may need additional time to practice them. Some modifications, such as Laura’s limp in The Glass Menagerie, may not need much additional time, as the actress playing Laura can work on most aspects of the limp privately in her own time. However, the actor playing the title role in The Elephant Man needs to contort his body sufficiently that extra rehearsal time is probably required.

Mind-altering conditions. Scenes where an actor is drunk, high, crazy, or mentally challenged may need some extra rehearsal time.

Playing multiple characters. Some people are very skilled at this and don’t need any additional time to rehearse. However, actors who need assistance in creating clear identities for multiple characters, or who need to switch between them within a single scene, such as in The 39 Steps, benefit from additional time.

Plays requiring perfect timing or which rely on speed. Not only does this include farces, but it also includes episodic plays like The 39 Steps and The Front Page, wherein much the fun and humor is dependent on fast-paced timing, both of lines and physical action.

Plays requiring perfect timing or which rely on speed. Not only does this include farces, but it also includes episodic plays like The 39 Steps and The Front Page, wherein much the fun and humor is dependent on fast-paced timing, both of lines and physical action.

Love scenes. In theory, this shouldn’t take any extra time unless the scene is lengthy and requires a lot of physical movement, in which case it is much like a dance. However, some actors have more inhibitions about the level of intimacy required by a love scene than others, just as some plays are more demanding in this regard than others. Bell, Book and Candle is a good example of a play that requires considerable highly-charged physical intimacy. If the actors playing the lovers are at all shy about entering into the demands of the scene, rehearsing them early and often to allow the actors to achieve familiarity with each other and comfort with the physical contact is the only way to make them believable.

Foreign languages, accents, or gibberish. A play like Enchanted April, if you have a non-Italian speaker playing the role of the cook/housekeeper who only speaks Italian, may need a little extra time, although much of her work will be done outside of regular rehearsal time. Plays where all the characters adopt an accent, such as British English (Received Pronunciation) may take extra time to teach the cast the rules of the accent and correct them when they go astray. Plays like Woman in Mind, the opening scene of which is conducted partly in gibberish, take additional time to rehearse, to get the actors comfortable with what the gibberish is supposed to mean and how it is to be delivered.

Classics. Playwrights like Chekhov, Shakespeare, and Moliere present their own performance challenges that might warrant an extra week of rehearsal.

Children. Depending on the age of the children and their level of experience, it may take a little extra time to get them to understand what they need to do.